Steering for social practices

According to the lens of social practices, our daily doings largely consist of routinised actions that we hardly consciously think about. These patterns are usually not the result of conscious choices, but are mostly maintained by social and material structures in our environment. Consider, for instance, the norms we share with people around us, and the way our physical environment is laid out. Maybe you stop by the supermarket after work because it is on your route home. And at the checkout, you naturally join the queue.

Municipalities struggle with making policies for (more) sustainable consumption practices, because steering now often focuses on behavioural change. If we want everyday patterns to become more sustainable, policies should focus not (only) on conscious motivations but also on the social and material environment in which that behaviour takes place. How can we create an environment that nurtures sustainable practices, and makes it harder for unsustainable habits to persist? In this study, we have developed several lessons on how municipalities can manage practices. In addition, we investigated how governance is influenced by what civil servants consider to be the “normal” way of working in municipalities, which we refer to as governance practices.

Lessons for this line of research come from workshops with officials, interviews and ethnographic research (walk-alongs and co-designs) at three municipalities in the period 2021-2025. However, lessons on policy and steering also follow from the co-creation of interventions in the food and energy line in which we collaborated with various public and private stakeholders to design tools for steering practices. For more information on the methods, please refer to the reports on the downloads page.

Steering programmatically

The environment that shapes our daily lives consists of many different elements, such as values, norms, beliefs and cultural expectations, but also tools, infrastructure, devices, skills and know-how.

Moreover, those elements are interrelated and mutually reinforcing. So if you want to influence that environment, you often have to act on several things at once. For instance, if you want people to separate their waste better, you should not only work on the standard ("that's how it should be"), but also make sure the right tools are available and that people know how to use them.

In other words, interventions in social practices usually consist of a bundle of different interventions that need to work together. This is one reason why a programmatic approach is important for making social practices sustainable.

It is also important that different sustainability issues are interrelated. For example, choices about making homes more sustainable should be aligned with the municipal vision for heat supply and climate adaptation.

In practice, we see that sustainability measures taken by municipalities are often ad hoc. For example, isolated actions are organised because a specific subsidy is available for them at the time. There is also a lot of project-based work, but often without a clear interrelationship being organised between projects.

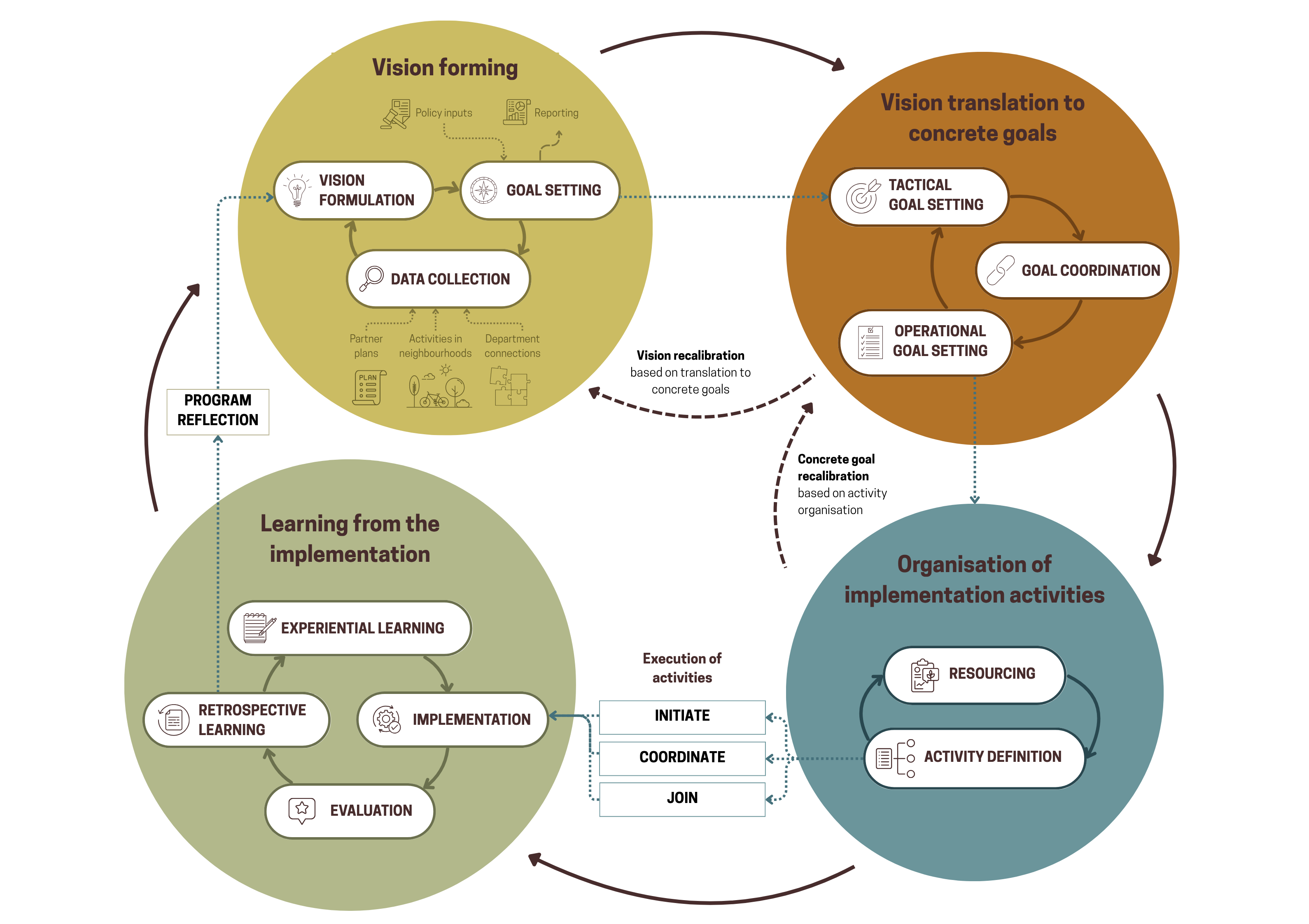

To make the idea of 'programmatic steering' concrete, in this project we worked with officials to develop hands-on ideas for how to shape a programmatic approach. In working sessions, officials, under the guidance of researchers, modelled a programmatic approach as a system of activities composed of four so-called cycles:

- Setting societal goals - The municipality formulates the higher societal goals it wants to achieve with the programme. These goals are attuned to laws and regulations, administrative wishes and what is going on in society.

- Tactical goal setting – The societal goals are translated into tactical goals. This involves coordination between municipal departments and with external partners. This coordination can lead to societal goals being adjusted. This creates an iterative interplay between societal and tactical goal-setting.

- Setting up activities - Tactical goals are translated into concrete activities, which also require staffing and resources to be organised. Again, the translation process may lead to the adjustment of tactical goals, which creates a second iterative relationship.

- Learning from implementation - Activities can be implemented in different ways. Sometimes the initiative lies with the municipality itself, sometimes with partners or residents. What matters most: learning from implementation. This can lead to adjustments during implementation, but also to reflections on the societal goals. By actively linking learning processes to the content and direction of the programme, a learning programme is created.

Integrated steering

A second theme is integral steering, which is closely related to programmatic steering. This is because the activities within a sustainability programme are likely to spread across several policy areas and thus affect different departments of the municipality. Moreover, some activities are better carried out by cooperation partners outside the municipal organisation. Implementation thus becomes a shared responsibility of various municipal departments and external partners. But how do you organise implementation in an integrated way?

In the project, we discovered that integral steering is strongly linked to a sense of ownership. Simply 'placing' activities and responsibilities with other departments or partners often does not work - they then feel little connection with those activities or the underlying objectives. On the contrary: it is quickly perceived as extra work on top of the existing range of tasks.

What does work is having an open conversation about the issues on which the programme focuses. If different departments and partners identify with such an issue, a shared sense of ownership is more likely to emerge. From that, we can then jointly deduce what the shared challenges are, and how the approach can be organised.

One of the resulting recommendations is therefore to gather departments and partners around shared issues, rather than predefined tasks. From there, they can jointly determine what activities are needed - and who can take ownership where.

The programme-based approach we developed together in this project allows for this, because societal and tactical goal-setting are not purely top-down, but can be fed through a learning cycle by insights from concrete activities.

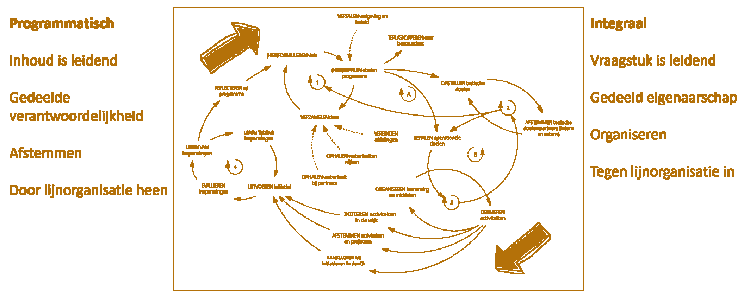

In this sense, programming and integration are two sides of the same coin:

- Programming describes how substantive ambitions come about and lead to a coherent set of activities.

- Integrated steering describes how shaping those activities together in shared challenges provides a substantive breeding ground for the programme.

Partnership

In the context of programme-based and integrated steering, the term 'partner' has already been mentioned several times. A programme of activities often contains elements that can be better carried out collaborators than by the municipality itself. Sometimes this is because of their substantive expertise, but it may also be that the municipality simply does not have the necessary capacity.

To implement programmes of activities integrally, it is therefore important that the municipality knows how to work in partnership. However, partnership is not something you 'arrange' with a signature on a cooperation agreement - it is a learning process in itself, requiring customisation and time investment.

In the project, we therefore also addressed the question: how do you organise that partnership? Based on our experiences, we share three key lessons below.

Lesson 1: Engage in the conversation - and keep doing so

Regularly engaging with (potential) partners. In our experience, there are many pairing opportunities, and there is often a lot of willingness to cooperate. But, in the daily hustle and bustle of work, these meetings do not come about naturally. So here too, changes in routines are needed: organising regular meetings, exchanges or 'work tables' should become a more natural part of municipal work.

Lesson 2: Build on existing momentum

Instead of asking partners to participate in completely new initiatives, it is more effective to look for points of connection to what is happening. So linking opportunities, moments when ongoing initiatives by different parties can reinforce each other.

In every area, people and organisations are active in many ways around a variety of issues. Instead of competing for attention and energy, it is more powerful to bring commitment together and mutually reinforce it, making cooperation more natural and effective

Lesson 3: Dealing with different interests and public value creation

Working together also means dealing with different interests. The municipality works from programmes with political and legal objectives, while partner organisations have their own mission, vision and considerations. These interests can fit well together, but can also be at odds.

It is important to discuss this early and openly: what drives different parties, what is at stake for them, where are possible points of tension, and where is room for alignment?

To prevent the conversation from getting stuck in contradictions, it helps to reflect together on the public values behind those interests. Public values are the societal values we collectively strive for - think liveability, sustainability, health or justice.

Shifting the conversation from concrete interests to shared public value often creates space for new connections. Sometimes this leads to the conclusion that cooperation is not (yet) possible, but often it turns out that seemingly clashing interests serve similar values that provide a solid foundation for partnership.

Participation

Partnership can also take the form of participation, as residents play a role in many municipal sustainability activities. In recent years, there has been a lot of focus on participation as part of addressing social issues. Sometimes, participation even seems to become an end in itself. This entails risks, especially when participation processes are set up without it being clear what kind of input from residents is possible or desired.

Participation can also mean the municipality joining existing initiatives by residents, an approach also known as 'government participation'. Which form of participation is appropriate requires careful consideration. Co-creative forms only make sense if there is actually room to do something with the results. If it has already been decided that a neighbourhood should 'electrify', it makes little sense to ask residents about their dream images for the future heat supply. Such processes mainly reinforce the feeling that participation is just for form's sake.

Expectation management is crucial, both among residents and within the municipal organisation. What is the real space residents have to influence? And via which concrete paths can their input actually land in policy or its implementation?

A programme-based approach makes additional demands in this respect. In a programme, several issues and activities hang together. Within those issues, the municipality encounters the same residents at multiple times and in multiple ways. The coherence of the programme therefore also requires a coherent approach to participation. Not as a separate intervention, but as part of a long-term relationship that the municipality builds with residents.

So a clear vision of participation is very important. Not just on paper, but especially as a vision that is lived through and shared by officials. In this way, residents are consistently involved and participation becomes a conscious choice that suits the nature of the activity and the space that is actually available for influence.

A learning process

Our ideas on programmatic and integrated working, partnership and participation were developed in close cooperation with municipal officials and their partners. The research itself is therefore also an 'intervention' or co-creation of new governance practices. That collaboration took the form of a joint learning process that has no clear end. The insights we share here do not constitute a conclusive list, but they are the outcomes of a learning process that is still ongoing.

In a broader sense, this also applies to guiding social practices, which are not entirely ‘engineerable’ and to some extent have a life of their own. A programme-based and integrated approach creates a fertile environment for more sustainable practices, even if the outcomes are to some extent unpredictable. It is therefore important to continuously learn, evaluate and reflect on the approach and its underlying goals. In short, we continue to learn by doing.